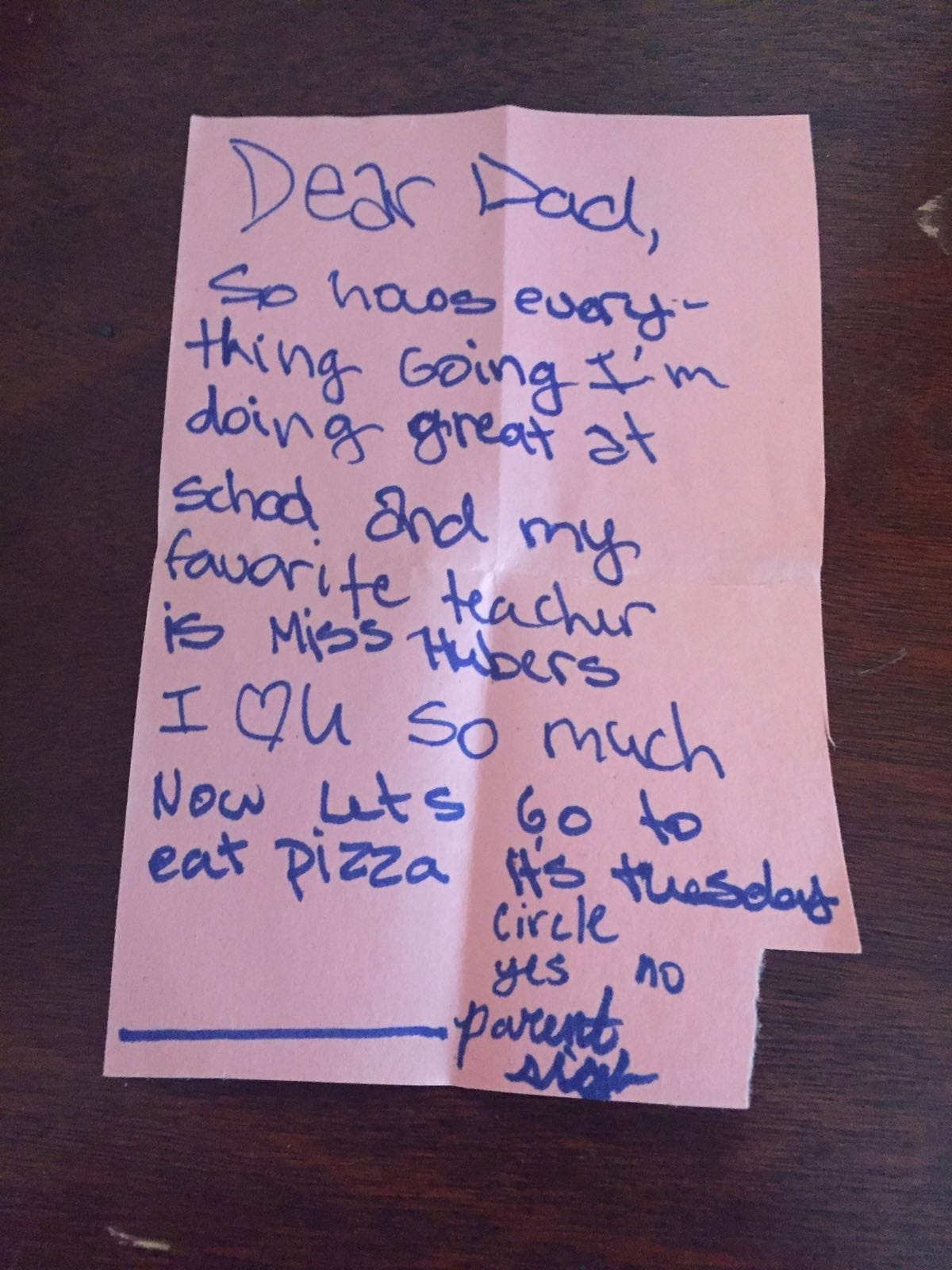

When I was in the fourth grade my class was assigned the task of writing a letter that would be read in 100 years, presenting a depiction of what life was like in 1999. For no other reason than my own curiosity and boredom, and because I didn’t think there was anything written on wide ruled notebook paper worthy of future preservation, I decided to make it look like it was written 100 years prior. I took a bunch of sheets of copy paper and soaked them in that day’s batch of 4C Iced Tea. Of course they all stuck together in a sugary mess when I set them out in the sun. Bad idea. On my second attempt, I used coffee. I hung the paper on the clothesline, crumpled it up, ironed it, gave it some tears, and burned the edges off so that it looked like the Danglars letter in The Count of Monte Cristo. And if we’re being honest, the contents of my letter were likely given far less thought than the actual design. I had already burned through all the mental gas in the tank brewing coffee for the stationary. My teacher was nonetheless equal parts confused and impressed by the unnecessary steps taken to complete the assignment.

“How’d you make it look like this?” she asked.

I gave her a somewhat smug double eyebrow raise, “Smell it.”

She held the paper up to her nose and gave it a whiff. “Coffee?”

I marveled at my ingenuity. At the time, there was no googling, “How to make paper look old,” so I thought it was a novel idea. And even though the assignment did not call for these extra steps in design, it automatically landed me an A+. From that point on, I spent my weekends blowing through all our Cafe Santo Domingo and almost setting the house on fire with my new stationary factory.

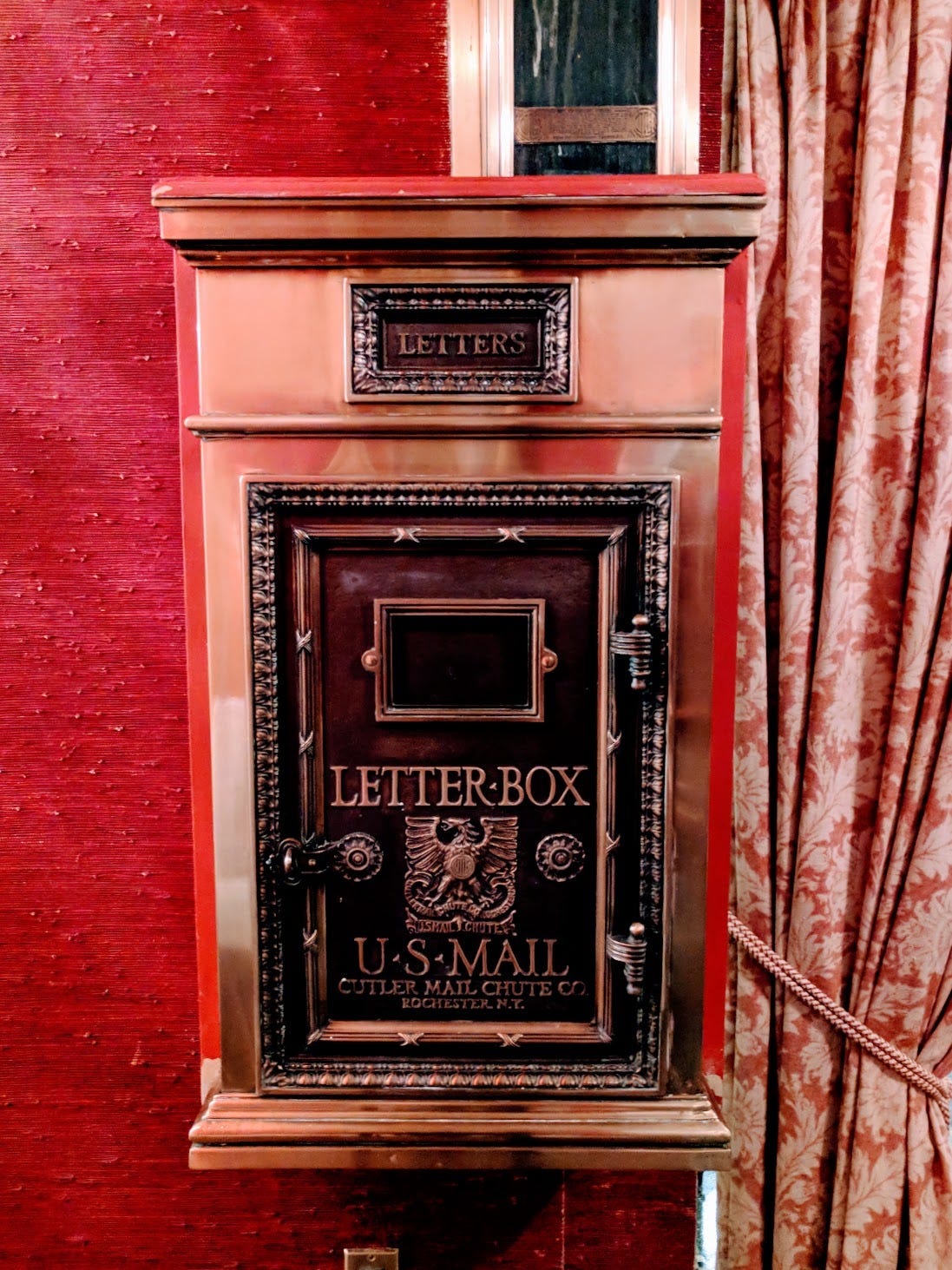

Later in the semester, our teacher had introduced the postal service into our classroom. We all made our own mailboxes out of old cereal boxes, decked out in our best stickers, glitter, sequins, and multi-colored paper. Extra credit provided us with our own classroom postage. POSTAGE! And we would deposit letters into the big bin at the front of the room for that week’s “mailman” to deliver once per week. My husband often tells me about, “The year I fell in love with Cinema” and all of the films that contributed his transformative experience. Well, 1999 was the year that I fell in love with the postal service.

I had given birth to a lifelong obsession with correspondence, its changing of hands over time, its evolving texture, color, smell—each crease, tear, and stain full of stories that beckoned to be explored. Letterheads, fountain pens, pencils, charcoal, typewriters, paper chutes, markers, plumes! …all leaving their own histories on the blank sides of their canvases.

I buried time capsules around my backyard, slipped notes into books I returned at the library, wrote countless letters to classmates, pen pals, relatives, crushes, and teachers. If I had a message to get across, it was going to be written on my finest paper, neatly folded into an envelope that I cut and folded together myself, sprayed with my mother’s Chanel No. 5 (or, if I couldn’t get my hands on that, a piece of the living room potpourri), and sending it off.

Of course, my correspondence only made it so far, and that is likely why there was the fascination with it. Growing up in the Dominican Republic in the nineties was difficult for a girl that loved the postal service. The country’s system for mail was and continues to be close to nonexistent compared to what we have in the United States. You don’t simply pop a letter into a mailbox in Santiago and expect your friend in Santo Domingo to receive it in three to five business days. If you are sent a postcard from overseas, you will get it months after that person has returned from their trip. Our utility bills often came in the form of carbon paper rolled up and shoved in between the holes of our front gate. As a matter of fact, I don’t think I have ever seen a Dominican postage stamp, even though I am marginally aware of their existence. The only packages you got from anywhere came wrapped up in the suitcase of someone who just flew in from New York or Miami. That or the Scholastic book fair organized by our American private school (likely via US address and then forwarded to our school) which, like pay per view, was a luxury my parents never let us partake in. As revenge for this childhood deprivation, I find myself wantonly subscribing to TV channels and buying books I watch collect dust on the shelves before I finish the one I have been reading for four months. And when we moved back to the States in 2003, I started a five year correspondence with my cousin in Queens whom I spent time with regularly, but who nonetheless was the greatest pen pal to talk about the most trivial things with. I spent my money on stamps and bubble gum between the ages thirteen and eighteen. Those letters, addressed to each other by our names with the surnames of our celebrity crushes, are still some of my most cherished possessions.

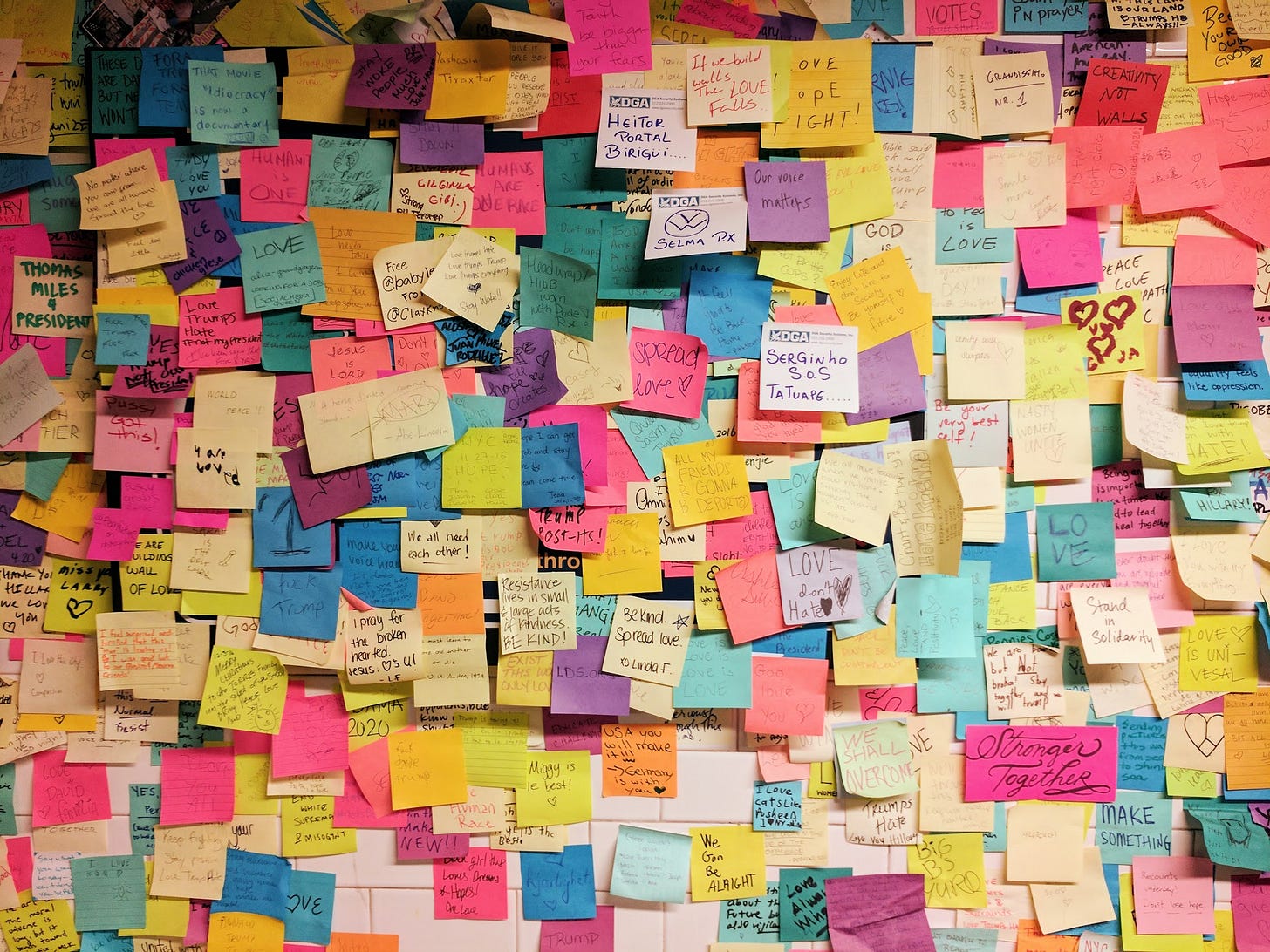

Why is physical correspondence something that is romanticized in the age of rapid communication? I say romanticized because it doesn’t seem to go beyond that anymore. We love the idea of buying beautiful ultra fine paper only for it to sit untouched in our desks while we send each other memes all day. There has never been a time in history that humans en masse have had such unremitting access to one another and to unlimited information, but with so very little to say. The trouble is that we aren't all filled with brilliant thoughts in every moment of our waking lives, even though that’s how often we’re communicating our thoughts. This makes for the quotidian conversations to be, as my mother says, mucha espuma y poco chocolate. Fluff. There is almost always a better use of our time than laughing at reels we have seen saying the same things via 100 different accounts.

My love for sending and receiving letters never wavered. I go to the post office every chance I get, namely those still housed in their neoclassical marble-faced buildings, tall ceilings that make the sound of your heels echo through the corridors lined with brass PO Boxes. I wish I received more letters, but I find that there aren’t too many people as interested as I am in sending them. Aren’t we all longing for the return to a physical connection with one another? To put things on paper? To say, Hey, I picked this fleur de lis stationary because I know how much you like the color burgundy. And when I bought it at Scriptum in Florence, I was only looking to escape the heat by finding some respite in their air conditioning. I spoke to the shopkeeper about the factory in which the stationary is made. I bought two posters of Sofia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni, and since she knew I’d be traveling, she carefully wrapped them in wax paper and slipped them into a cardboard cylinder. She asked me where I was from and told me about her first time in New York. Are we no longer excited at the possibility of storing our letters somewhere in an attic so that twelve years later, you can come back to them and laugh, or be filled with melancholy, or in some cases just be repulsed?

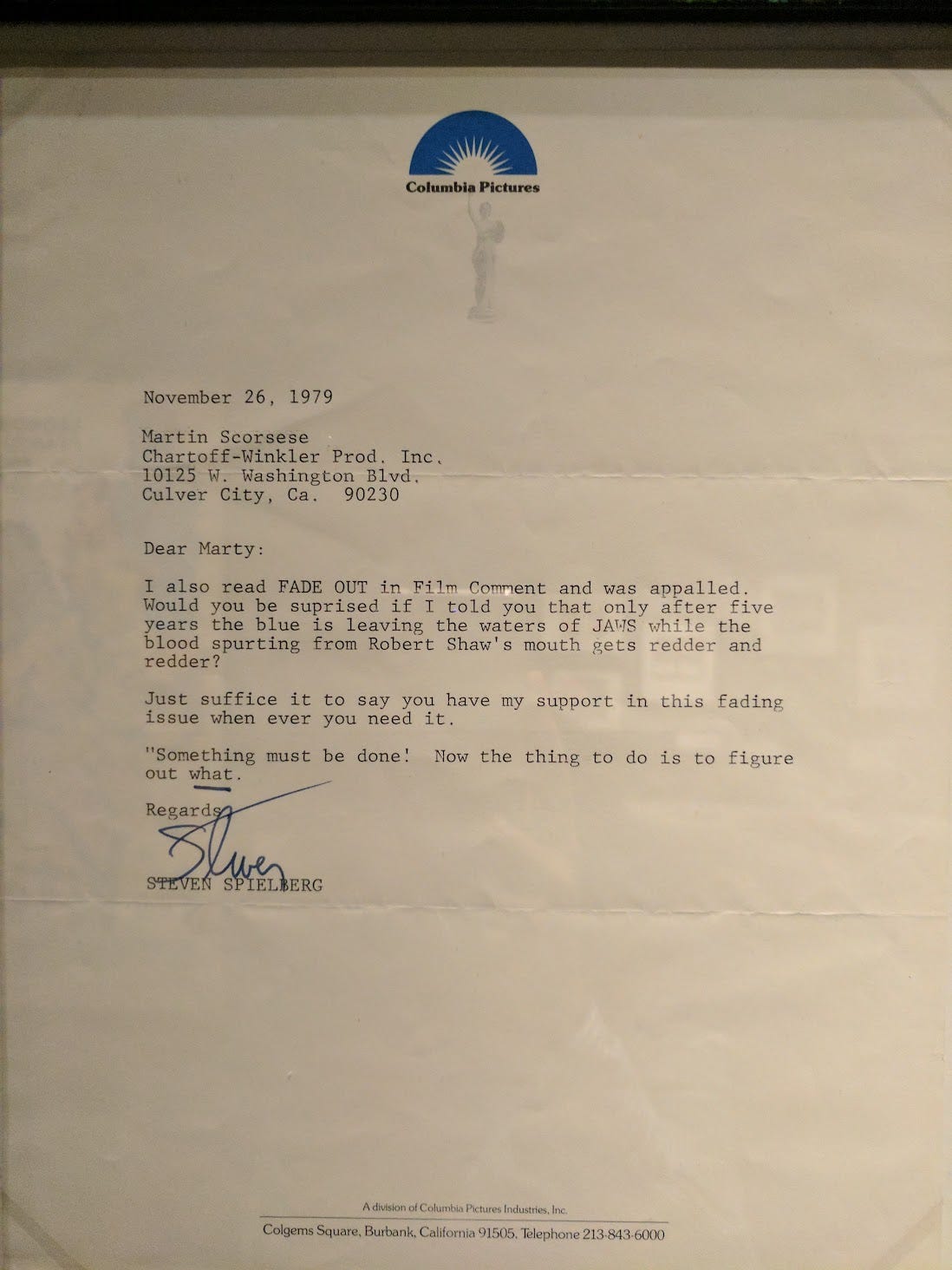

I like to think of correspondence as our own little artifacts. I don’t think we are so conscious of that when we pour ourselves into a journal, write down a shopping list, send someone a birthday card, or dedicate a book to someone. But to memorialize your words and your penmanship on a piece of paper that will outlive you is its own form of history; something that someone, someday, in some capacity, can and often will reference. They will look at the weight of your lines, the ink, the color of the paper, the pop culture references, the pain, the joy, the uncertainty.

I recently had the pleasure of reading Annie Atkins’ Designing Graphic…where she details the research that goes into the defining of print media for film. A great deal of that research comes from yard sales, antique shops, libraries, and used book stores where you are able to tangibly interact with artifacts in the form of postcards, movie ticket stubs, a shopping list used as a bookmark in an old cookbook, or a letter written by a civil war soldier to his wife directing her on handling their affairs while he was away. Letters can inform us on how penmanship evolves over time, or tell us, perhaps, about the writer’s socioeconomic background. They can inform us on common courtesies, manners of speech, or contain lurid revelations, like the letter found between the pages of a Bible I bought at my late neighbor’s tag sale, divulging an affair she had with her priest sometime in the sixties. But beyond being a point of reference, they create a bridge between ourselves and omnipresent souls in the same way that the columns of the Pantheon and the layers of lead paint in a Manhattan pre-war do. We are only stewards of the things that will remain here after we are gone.

When I wrote my hundred-year letter in the fourth grade and dyed it with coffee, I was trying to make something that I felt would connect with someone more than a regular piece of wide-ruled paper that I ripped out of my composition notebook. I wanted to make an artifact. And even if from afar it didn’t look like something of the same period as The Backstreet Boys, it would inevitably have been given away by my handwriting which was so of the period. And that’s because we unwittingly leave behind so much of our personal footprints in everything that we touch with our own ink on paper, something that cannot be said for a screenshot of a text message sitting in the enigmatic cloud.

This entry in the Knickerbocker Sketchbook is the first in print media as artifact series.